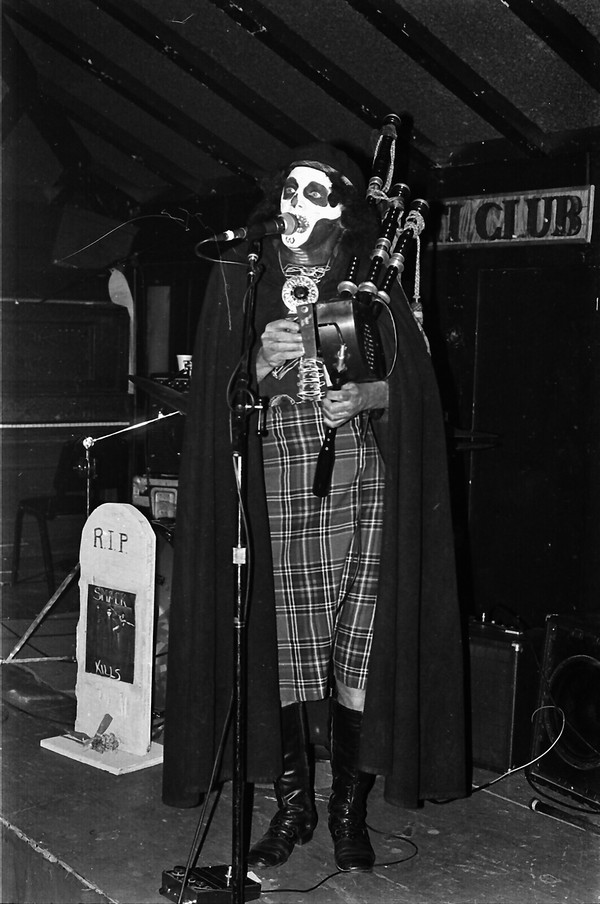

Jimmy Smack — Death Is Certain. A story of Los Angeles’ 1980s rockstar

As trite a reference point as it has become for white western audiences, there is something of the shamanic in Jimmy Smack’s music. Not to imply that he takes on the same, solemn spiritual role, nor to intend any offence in offering this reading. He is the kind of singular figure that only a setting like 1980’s LA could spawn from its sewers to carry a bleak prophecy. A character birthed from the dream factory’s effluent; a fully fitting totem for its time and place.

Ultimately, LA as a locale is synonymous with both its obsession with ascension, achieved via celebrity, and also the overwhelming proclivity for self-immolation that it’s pursuit carries. In the 1980’s, the glittering veneer of decades previous had worn off in LA. The drugs had gone bad and police choppers predatorily circled like vultures overhead, leaving a skeletal, urban nightmare writhing below. Internationally, many were introduced to mid 80’s LA through its prominent depictions in pop culture — namely nihilistic film and degenerate punk. Films like Falling Down, The Terminator and the sprawling drains of its sequel etched mental maps of what LA looked like and represented; a lawless concrete jungle. Viewings of cult classics Repo Man, Suburbia, The Decline Of Western Civilisation, et al populated these drains with a host of punk mutants, both real and imagined, that lurked behind every graffitied alleyway waiting to inflict violence. These films captured on celluloid a zeitgeist to which Jimmy was, at the very least, adjacent in its inception, his corpse-painted face could be convincingly lurking behind any of their dimly-lit dumpsters.

There is no doubt that he was firmly adjacent. Not only was Jimmy a decade or so older than many of the punk peers he would share the stage with, the total outré nature of his performance meant that it would never be as easily digestible as the SST bands who co-habituated his Star Theatre performance space as their rehearsal rooms. Be it Minutemen’s politico agit-punk or Saccharine Trust’s almost proto-emo, it’s clear that Smack’s macabre rituals were always going to be occupying another plane entirely.

“He (Mike Watt of Minutemen) lived there for a while. Black Flag, Minutemen… I let them rehearse there and stay there for a while. We had concerts there for a while. Then the locals jumped in on it and there were gang fights, helicopters surrounded the place and the black and whites (cops). So, I just had a gang powwow with the locals and then told them I’m just not going to do any more concerts and what not, not wanting to cause any more trouble. You know cuz I had the Theatre and our school dance classes were running out of the Theatre and all the sudden people’s kind of tripping on me cuz I was different.”

From 1983’s Death Rocks 7”, Hating Life more comfortably locates Jimmy within the punk, and later KBD, lexicon. It’s pounding rhythm and repetitive melody sitting alongside Daily Fauli’s Speed as a classic piece of negative minimal-wave. Similarly, Hating Life possesses the same misanthropic thrust as The Nubs’ degenerate anthem, Job, just without the guitars.

“What’s weird is that (he points to his tattoo on his upper arm of a reaper) that’s what I became. I got this tattoo first. This is from one of the finest tattoo artists in the West Coast, Mark Mahoney, when he was in Long Beach. When he just got here from New York, CBGB’s. And it was strange that I just became this tattoo. And then of course being in San Pedro where everybody was doing punk rock avant-garde music, I just fell in with the crowd.”

The rest of Jimmy’s work edges closer to the precipice of avant-garde, his instrumental cacophony often serving as a canvas on which he lashed his own poetry and performance art. Just as Arthur Brown scorched himself into the retinas of 60’s England when his Fire burst through Top Of The Pops, as did Jimmy’s spectral visage when it was foregrounded in a 1985 Spin magazine article covering LA’s Deathrock scene. Similarly, Jimmy’s live rituals cut a similarly standalone figure to the rites observed by obscure 70’s Australian experimental performer, Geoff Krozier. Although clearly spread across disparate contexts, all three artists share a common iconoclasm in their fully realised combination of subversive sound, occult vision and bloodyminded intent.

“I was a classically trained dancer, I was in the theatre all the time, my whole life. I had the Hollywood Free Theatre and then the Star Theatre. I was just always on stage doing something. Worked with all these clowns, we were all clowns so I became a clown — I was Jimbo the clown.”

While unique in his approach to the form, Jimmy was still undoubtedly part of the short-lived Deathrock movement that bore groups like Christian Death and 45 Grave and attracted slews of disaffected, heavily made-up outsiders to inhabit spaces like the Anti-Club.

“(I played) everywhere: Anti-Club, Club Lingerie, Club 88, Troubadour. Once I got hot it was like I could play every weekend. People were pulling on me so I just kept on. Then I started getting some death threats and you’re pretty vulnerable on stage. So I was supposed to play that night and then I got some death threats on the phone and being married and having children and stuff I thought man, maybe I better not chance this you never know. I was vulnerable. I bailed right after the death threat thing (1983). I stopped, sold my pipes.”

The connection with death states as a focal thematic concern in Jimmy Smack are clear. As they equally are in the shamanic tradition, wherein the shaman acts as a conduit between the living and dead, the inside and outside realms. The trancelike quality of the raga-leaning drum machine in Cybernetic and its accompanying bagpipe drone are one of the more prominent projections of bleak reverie found within Jimmy’s three short releases. From the same 1982 7”, Death Or Glory, Batty conjures a similarly purgatorial essence.

“I had a great highland war pipe, a really hard instrument to play, and they’re all made out of wood — you know — and they have little tubes made out of bamboo split up. They are long and vibrate, you got a bass Reed and tenor reeds And you have to make this vibrate at the same frequency. Just went up and down on the tubes, and the tubes are usually made out of ebony, some kind of African wood. It’s a double-reed instrument, like an oboe, vibrate with those reeds. I learned how to play that in the closet, and then I got to go out on the coast in Santa Monica. There was the Irish Imports place, and they had a pair of Caltronics Mark 3 electronic bagpipes. So I got those and I plugged them in and I never did stop.”

Jimmy’s electrified bagpipe is not only significant for its use as a singular sonic device in punk (at least as far as I’m aware), but also for it’s further connection to mortality — the significance of breath as ultimate catalyst. Other than his pipes, Jimmy’s message is carried via hellish, oratory sermons. There is nothing more significant to life (or it’s lack) than breath, so it is then fitting that his primary aural conduits rely upon it.

Where a shaman attempts to bring educational messages for the inhabitants of this world from their liminal travels, Jimmy’s was a much more nihilistic offering; exclusively centring itself on total oblivion. One clear way of framing the fixation on apocalypse is to place it within the cold war context of 80’s America. It does not take a great imaginative leap to hear a wave of carpet bombing in the relentless drum machine programming of tracks like The Scarlet Beast, nor to confuse from where the beast of its title hails. It is fittingly named to reflect the Reagan Doctrine era in which it was recorded, during which time the paranoid threat of communism loomed overhead. The track viscerally embodies the period’s abject fear of nuclear annihilation and invokes a feeling as dark as living in the perpetual shadow of potential war.

In more recent decades, LA has embraced a new spirit — namely the furthest excesses of branded wellness culture and the hollow rhetoric it can keep as a bedfellow. These exercises largely attempt to fill the void with consumption or appropriated processes of self-optimization. Rather than turning away, the LA Deathrock movement that Jimmy existed within welcomed the void, albeit briefly, with a hedonistic abandon. Jimmy himself choosing to greet the darkness of the unknown with an equally abysmal drone and expression of maniacal glee.

“Being a performer, you just give your all. I did that for years, I just gave everything I had you know, it was fun.”

On Death Is Certain, Knekelhuis gives Jimmy’s works the lavish display that they deserve. Here they serve as markers of time and place for anyone in need of reminder of his uncertain times, not wholly unlike our own. And, although he was always pre-occupied with the end of life, this collection fills his lungs once again.

Cooper Bowman

Newcastle, Australia

December 2021